On photographing men

Rimowa Design Prize Documentary, Filmmaking with Cyprien Bourrec and a daily motivational boost

Dear Subscriber,

I am currently in Paris, spending the month here. This time I wanted to try out something different to the last Newsletter, where I showed my process when creating a personal project. When looking through my archive, I realized how often I photograph men in my personal work. So this is an attempt to approach this pattern - not a statement, rather an investigation.

Current Thoughts: Photographing Men

Note: I write this from my subjective position as a cis-gendered male. I assume the gender identities of my subjects to my best knowledge. I don’t claim to represent the full spectrum of gender identities but see this as my personal perspective on an ongoing cultural conversation.

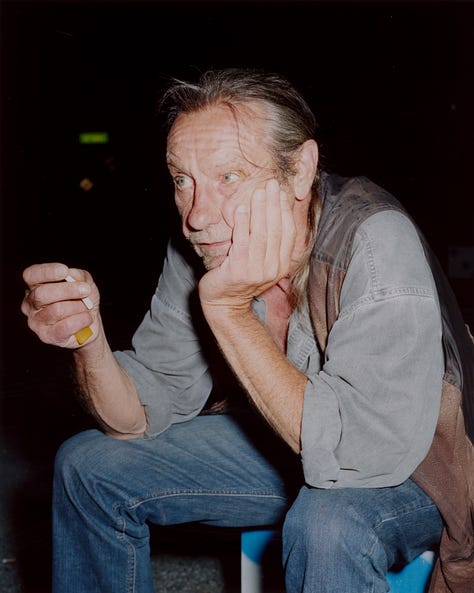

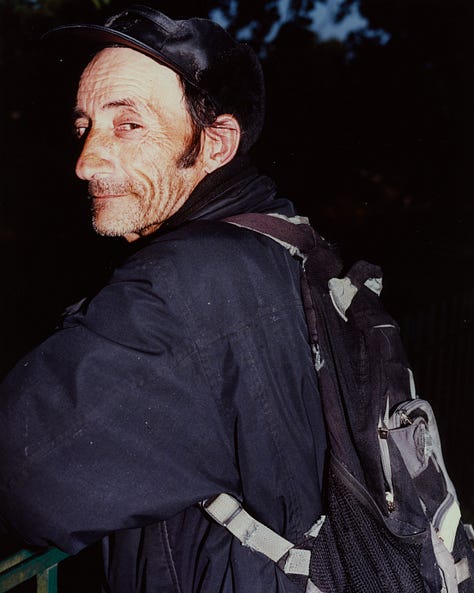

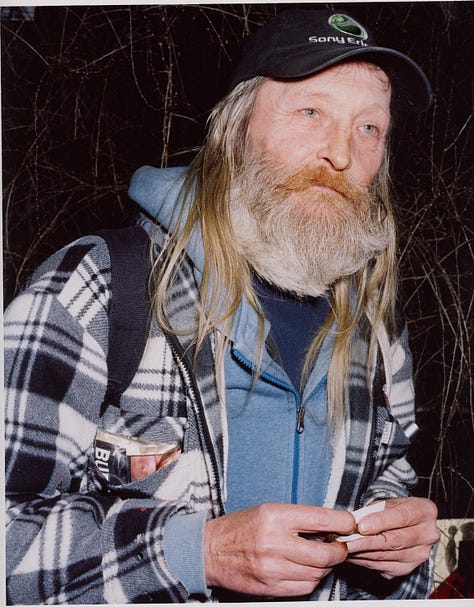

When editing my book Humpelfuchs, there was a brief moment where we considered including only images of old, seemingly lost men I photographed in Berlin-Neukölln at night. Since then I often asked myself what exactly drew me to these men in the first place?

Since I began taking photography seriously, I've been photographing men. While studying at the ICP in New York I met a German homeless man, that became my subject for a documentary. On one of our first assignements we had to photograph a stranger in their own home - I met a friendly older neighbor on my block in Bed-Stuy, who invited me to his home and I photographed him in front of his huge vinyl selection.

Masculinity is a subject that has attracted me sometimes consciously, but mostly unconsciously. I think a lot about masculinity in my private life, and I occasionally wonder how my focus on photographing men in everyday situations connects to this. When I look through my archive, what do I see?

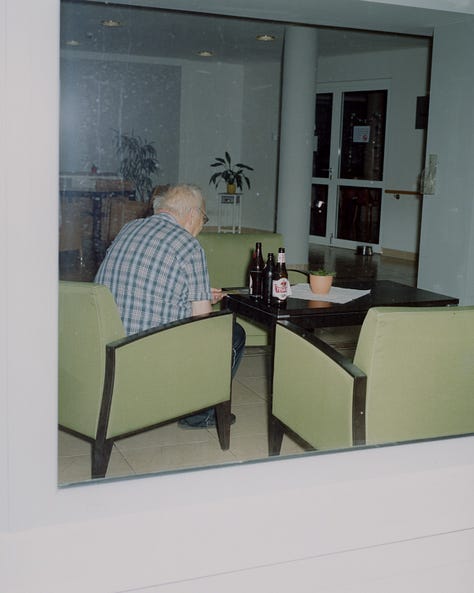

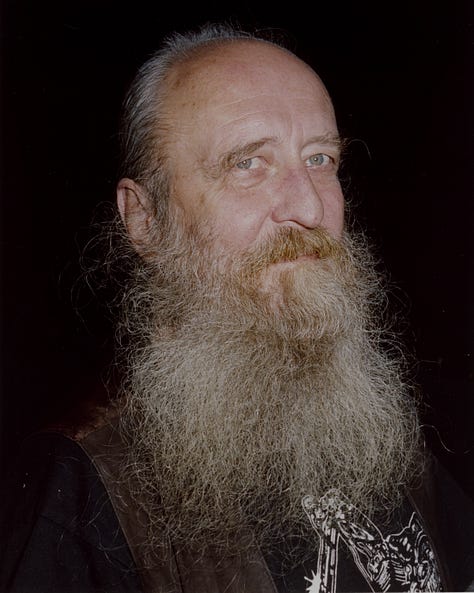

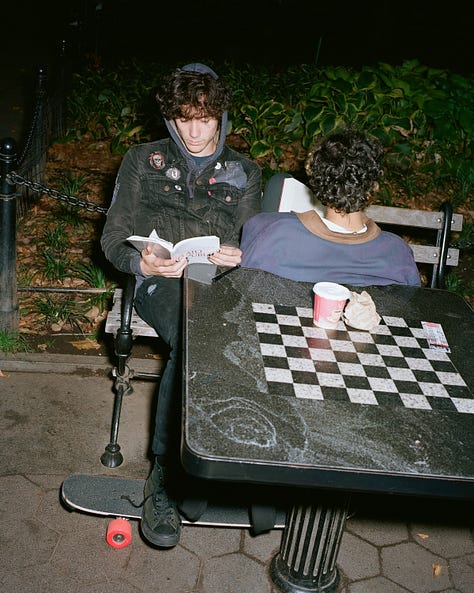

I see images of men in patriarchal positions but I also see men not fitting into these traditional roles. I see numerous portraits of old men. I see few images of young men. I see men at society's margins, smoking, waiting. I see men performing masculinity, for me and for the camera, for themselves, for others.

This last aspect particularly intrigues me. What makes a man? How do we present ourselves in public, and how does the world perceive us? For many men, this is a question they rarely ask themselves.

Through this newsletter, I'll explore what draws me to these subjects, what I find in images that often contain both strength and humor, and how my position as a male photographer shapes these encounters.

Part 1: The Gesture of Vulnerability

This image is one I keep returning to, when thinking about the men I photographed. In the background stands one of the anonymous housing projects in Manhattan. In the foreground, two men are visible, one sitting, one standing, in a close embrace, one apparently soothing the other. They're surrounded by metal fences, metal benches, and trees in full green foliage. Are we witnessing two lovers who have just found their way back to each other, or two friends consoling one another? I remember exactly the moment I took this picture. The fear of disturbing the moment, and how unusual I found this public display of affection. Men touching other men in public, giving and allowing closeness. I was afraid to photograph this scene, as I didn’t want to draw too much attention to them, but also was afraid, of making them feel exposed, of invading this emotional moment in public.

Part 2: Acknowledging and Projecting

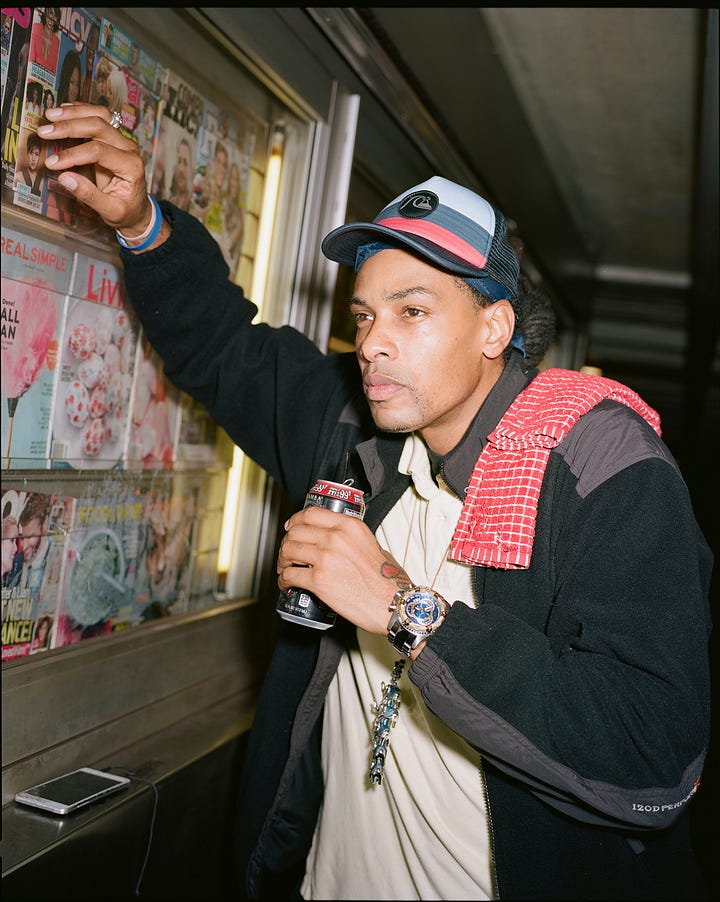

What does it mean to approach and photograph a stranger on the street? The photographer sees a face, a character, a style, something that stands out within the scenery. The photographed person finds themselves in a complicated situation. Unlike the photographer, they are unprepared, often alone, typically distracted from their everyday life and thoughts by being photographed.

I am often asked how I photograph people on the street and how people react. I take this as a compliment, because many of my images appear candid, but are mostly re-enacted. I've made it a habit to tell the people I want to photograph exactly why I want to photograph them specifically.

Yet I don't always know exactly what it is, because it's usually a mixture of different factors that draws me to the person. With most of these encounters, while working on Humpelfuchs, I felt that I had given them a kind of recognition through photographing them. Some men receive so few compliments in their lives that they remember a compliment decades later. The interest of a stranger may have felt like a compliment to some and perhaps like an intrusion to others.

In a way, the people I photograph act as a mirror - but not always. I see some part of myself in their life and photography can be my way of dealing with this part inside me. Of course, their seeming loneliness is a projection, but it also raises the question where does Life lead towards, as a man?

Part 3: Performing Masculinity

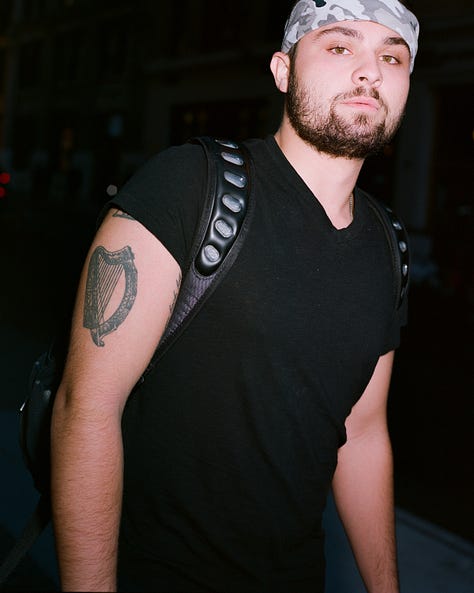

Is masculinity changing? Yes, in my opinion, for both better and worse. On one hand, I see male friends with kids performing so much care work as never before done by any previous generation (of course this should be the norm, but it hasn’t in the previous generations). On the other hand, there are figures from the manosphere like Elon Musk and Andrew Tate, who target young men with their crude theories about sex, gender, and feminism, striking precisely at the vulnerable spots in young men's souls. Men perform being men. It's exactly this performance that interests me. But what does it look like? A series I keep returning to was an assignment given to me by FAZ Quarterly in 2019. I spent a month in New York and was tasked with photographing the 'Man of the Future.' Impossible. I set out in search of men I found interesting, who performed or staged a kind of masculinity that broke with the 'ideal image' (my subjective ideal).

Often men perform their man-being with little self awareness. This subconscious performance interests me. It’s a contradiction between outer strength and inner insecurity. Maybe I photograph men to understand my own gender-performance? What is ‘too masculine’ and what is ‘too little’?

Who am I in this?

As a man, I view the men I photograph through different lenses. Perhaps I project onto them primarily a possibility (to become like them) or a deficit (that I perceive in myself). In any case, I want to approach them without prejudice and show them the recognition they deserve. I see men and the notion of masculinity in a crisis that won't be resolved through current social debate alone. A solution will only emerge when men speak with each other, about each other, and begin taking the many small steps needed to exit this cage of patriarchy. I'm particularly interested in men who challenge and question their own position.

So what draws me to men? I don’t think I can fully answer it. There is a tension, inside me and inside society, and I see my pictures of men as a way of dealing with this.

Writing this I wonder: what images of Masculinity do we miss in visual culture? I’d be happy to hear your thoughts.

A few resources that inspired me to reflect on masculinity

Mannsein heute – Zwischen Stärke und toxischer Männlichkeit - Sternstunde Philosophie (German)

Toxic Masculinity - This Jungian Life

The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men by Robert Jensen

Current Project: Rimowa Design Prize

Wallpaper* Magazine and Rimowa asked me to direct a documentary following the ten finalists of the Rimowa Design Prize 2025. I was instantly in when they told me that they secured access to the iconic Bauhaus Dessau building, where the first Bauhaus university had its origins. The ideation process took form in several concepts, drawing from the images the first Bauhaus students took of each other in the building. We separated the finalists into two groups, talking about the legacy of the Bauhaus and about mobility, the topic of the Rimowa Design Prize. Cinematically, we referenced iconic photographs (especially on the balconies) and had them explore the space; in the edit we went back and forth between the historical place and the fresh perspective the students give. Director of Photography on this was again my long time collaborator and friend Philipp Lee Heidrich (full credit list is on my Instagram).

Five Questions with Cyprien Bourrec

Cyprien and me met through our mutual friend Felix. Cyprien once gave me shelter from a catastrophic thunderstorm while I was camping in Corsica. I've been following Cyprien's work from DoP to directing and love the way he manages to convey a story, an atmosphere through the camera and his work for me always feels very narrative based. You can really see, that Cyprien is a filmmaker by heart but also has a background in Art Direction and thinks further than the imagery. We sat down in Paris for lunch and I just ambushed him with these questions:

How did you get into filmmaking?

Quite random. I already had an interest in it as a kid, but never considered it a viable option. I studied Art Direction in Belgium and started working at the social media team of a fashion brand in London. It was the first time I saw this world up close – things I'd only seen in BTS images, suddenly I was in the middle of it thinking 'this is cool, but I have no idea what's happening.' I shared a warehouse with lots of freelancers back then. The living room transformed into a photo studio. The warehouse had a huge gate and within it a little door I'd go through like Alice in Wonderland, escaping the chaos of London into this magical world. With my flatmate Pierce Gabriel, we’d invite friends who were punks, DJs, and artists to the studio. Sometimes he would film videos, and I would take photos, sometimes the reverse. We had no idea what we were doing, but it was an amazing experience because there were no conditions – just experimenting.

How did you move from director of photography to being a director?

After about a year in London, I was done with the city – too much rush, not enough sunlight. I moved back to Paris to work as a freelance art director, which felt like an amazing newfound freedom. While working for Chloe, I started taking photos on the side that ended up on their Instagram. My boss surprised me by saying, 'You're going to be our in-house photographer and videographer now.' I protested that I had no idea what I was doing, but they still gave me a chance. Suddenly, I was shooting everything – digital campaigns, Christmas parties, backstage at fashion shows. I was in the middle of all these things I thought were impossible. But I learned fast, especially through YouTube tutorials whenever I wasn't working.

The brand sent me everywhere, Lanzarote, Sicily, Kyiv, London… Every location had a different context. It was phenomenal learning in such varied environments. Before Covid, people kept asking if I was a photographer or videographer, insisting I must choose one. During the pandemic, I had time to figure it out and decided to focus solely on video. I quickly moved from a one-man band videographer to Director of Photography, thanks to the many photographers I had met along the way. After working with bigger productions, I naturally moved toward becoming a director, which was always the end goal.

What's your directorial style?

I like to know where I'm going, but it doesn't have to be exact. I’m going to sound cliché, but my biggest inspiration was Lubezki's work with Terrence Malick on films like Knights of Cups, Song to Song – that was the first moment I thought, 'I can do it this way.' In those films, the camera is free, the actors are free. There's a frame and structure, but everyone can express themselves. It goes straight into poetic images where the camera and actors move freely within a basic framework. This approach showed me filmmaking doesn't have to be mathematical or rigidly planned. It can be fun.

For my commercial work, especially fashion, I apply this philosophy while dealing with practical variables – the weather, clothing availability, and tight shooting schedules. I always prepare a crazy shot list I can't possibly complete, so I can choose what makes sense in the moment. My list points in one direction, where I want to bring the video, but I keep the freedom to adapt rather than pushing for exactly what I had imagined. It's motivated by what's actually happening in the scene rather than forcing a framework onto reality. We make these films in one day – we don't have a week to say 'what if' – so this flexibility is essential.

Do you use your DoP experience when directing?

Never! Or so I say… As a DoP, your attention is set on a lot of technical variables. As a director, you need to forget all that or you're doomed – you want to focus on the person you're filming or the clothes or whatever the film's motive is. It's difficult, but I try. In pre-production, though, it's one of the most interesting parts when I talk with the DoP. We can deep dive into nerd talk beyond 'I want it to look soft’ – we’ll discuss texture, atmosphere, lenses, colours... All these crispy little details matter a lot to me.

What inspires you most?

Science-Fiction, world building, how a story can depict culture beyond just appearances: clothing, arts, language, gestures. In Dune and Andor, they really bring this to the foreground and make culture part of the story, which I find brilliant. In another domain, I love trees. Spring in Paris, one week you have buds, the next week everything is damn green everywhere. I find this sudden environmental change in such a short time super stimulating. And if I were to give one last, it’s people's dedication – the passion we put into things, how driven humans can be is fucking crazy. I find it fascinating how much time people dedicate to what they love; that drive is incredible to witness.

Monthly Discoveries

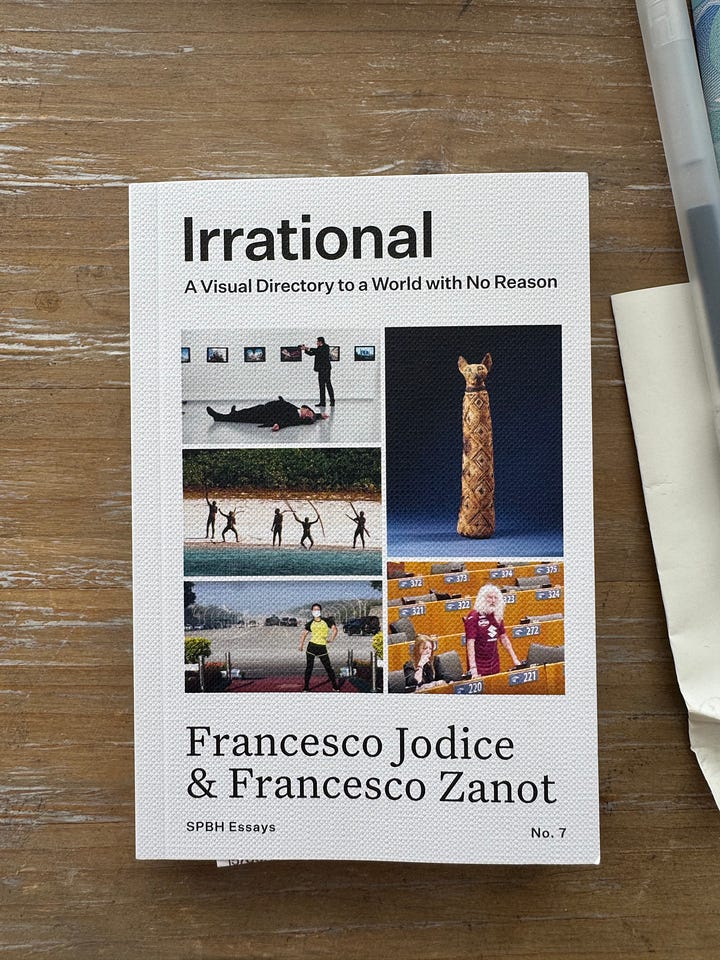

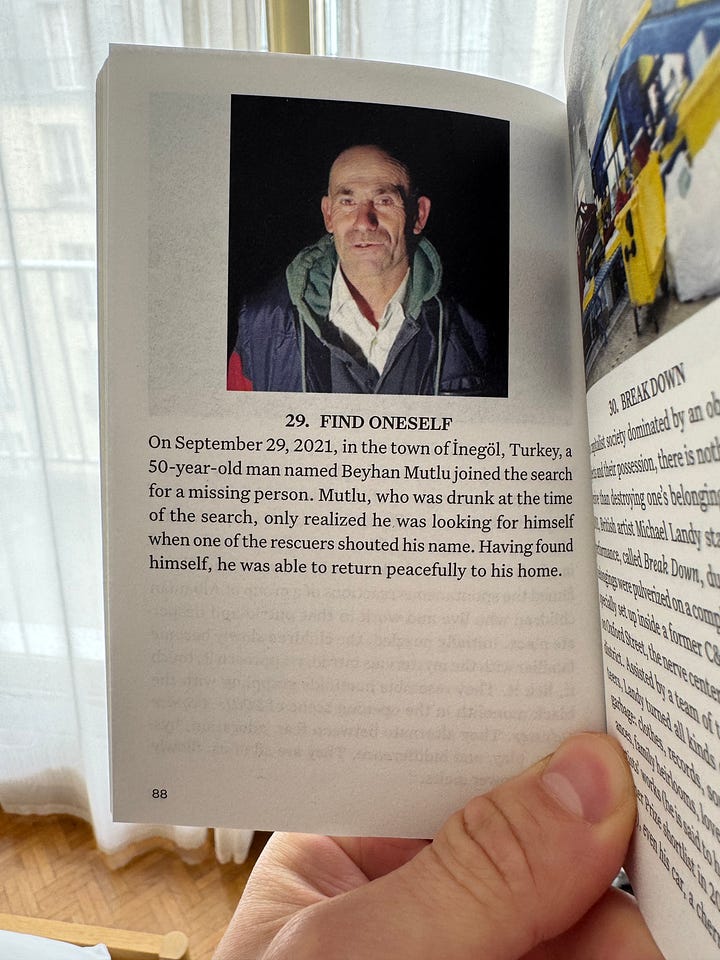

1. ‘Irrational: A Visual Directory to a World wih No Reason by Francesco Jodice & Francesco Zanot

Found this at Yvon Lambert in Paris. Lovely, horrifying accounts of irrationality in pop-culture, politics and news.

2. The most inspiring Instagram Account I’ve seen for months

3. Dreams by Akira Kurosawa

I was lucky they showed this film at Neues Off in Berlin beginning of May. Eighty year old Kurosawa stages the eight important dreams of his life. Maybe one dream for each decade? Fascinating to see how psychoalytical subjects (the mother) come up in his dreams and how events in his life (being a soldier, Tschernobyl) reflect in these dreams. Also the set design!

Looking Forward

What would you like to see explored in future editions? Feel free to reply directly to this email or comment on Substack. I'd love to hear from you.

Until next time,

Bastian

😍